The Price is Right: Essential Tips for Nailing Your Pricing Strategy

If you won’t take Price Intelligently Co-founder and CEO Patrick Campbell's word on the grand consequence of pricing strategy, heed the wisdom of Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffet: “The single most important decision in evaluating a business is pricing power,” says the Oracle of Omaha, ranking it above good management. “If you’ve got the power to raise prices without losing business to a competitor, you’ve got a very good business. And if you have to have a prayer session before raising the price by 10 percent, then you’ve got a terrible business.”

Over the years, Campbell has seen startups and multinationals alike labor to perfect products only to casually raise their finger to the wind when it comes to determining pricing. In 2011, Campbell launched Price Intelligently to help SaaS companies, such as Atlassian, Hubspot and Insightly, boost revenue from and knowledge of their users. Before that, he held strategist roles in the private and public sector: helping Google's mid-market advertisers grow their businesses via advertising solutions and serving as an Intelligence Analyst Fellow at the Department of Defense.

In this exclusive interview, Campbell deconstructs and walks through the elements of a pricing strategy to enable startups to more effectively acquire customers. The foundational work behind pricing is to create, test and refine buyer personas so that they’re mirrored on your pricing page. To do so requires a three-stage process: define your customers, collect data from them and apply your findings. While these steps sound simple, the execution is not. Let’s get started.

DEFINE YOUR CUSTOMERS

Perhaps you’re at a startup founded by people who’ve never handled pricing before or who are launching a product in a new market. Your first step is to begin by building quantified buyer personas, which are data-driven profiles of your target customers. The objective is to create categories of relevant and lucrative customer segments to determine the cohort that’s most important to deploy resources to pursue. Here’s how to begin:

Target 3-5 buyer groups to test. Especially at a company’s earliest stages, resources drive and determine decisions. “If you’re able to part with $20,000 to $30,000 to do a proper study of your market, skip to the next section. However, if that sounds like a lot to you, start small and pick fewer than a half dozen target buyer profiles,” says Campbell. “How do you do that? With an educated guess. In your early market conversations and preliminary prospecting, you’ve had an inclination that you’re selling to specific sets of people. Write down those groups, what you believe they value, what they don’t value and their willingness to pay. Note the group that you predict will have the most revenue-generating potential.”

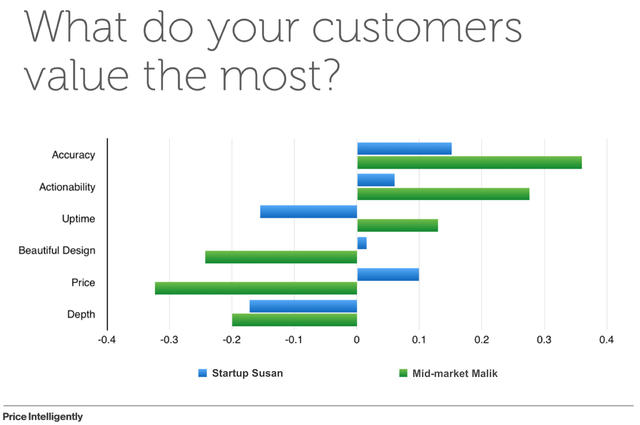

Christen each buyer cohort with a persona. Campbell is a fan of buyer personas, as used and refined by marketing automation companies, such as Hubspot and Marketo. His rule of thumb is to use an alliterative descriptor of each segment that follows this pattern: [group attribute] [first name]. “In the end, these are people, not numbers. Humanize your buyer cohorts,” says Campbell. “They could be personified by function, such as Sales Susan, Marketing Malik or Engineering Ernesto, or by stage, such as Startup Susan, Mid-market Malik, Enterprise Ernesto.”

This simple naming convention may seem silly, but it accomplishes a few, valuable goals. “First, it creates a common — and memorable — language for you to easily reference your potential customer groups throughout your organization. Second, it allows you to define and stack each cohort quickly. Lastly, it prompts you to recall the diversity of your buyer cohorts. It’s easy to imagine your potential customers as a vast ocean of people; this reminds you that each have distinct preferences, values and incentives that control their behavior,” says Campbell.

Assign descriptions — both demographic and behavioral — to each persona. Each target group should have succinct definitions that are relevant to your organization. For example:

Startup Susan - She’s pre-revenue or hits $1M in revenue. She’s not sophisticated with her processes yet, and is mainly focused on her core product.

Mid-market Malik - He’s a mid-stage company that's making $10M to $50M in revenue. He runs a team of 12 to 25 people.

Enterprise Ernesto - He might generate $75M or more in annual revenue. He isn’t likely going to use the product personally, but will more often be a decision maker.

These placeholder descriptions don’t need to be elaborate, but extensive enough so that you recognize them in the field. Identifying stage and behavior is a good place to start. Depending on the product, these descriptions might go deeper into what each cohort values, but the immediate objective is that your team can collectively understand each customer segment.

The bigger reason to establish this customer categorization is to begin to tackle one’s value proposition. “I’ve long believed that value is a spectrum. As human beings, we don’t inherently know the value of a chair or computer, but give it value relative to the objects around it. That’s just how we think, as has been proven out over years of psychological and economic research and studies,” says Campbell. “Given that, when you're looking at your customer personas — whether it's Startup Susan, Mid-market Malik, Enterprise Ernesto or other cohort groupings — the value for a particular feature is going to vary drastically relative to the different demographic or psychographic attributes of each persona. That’s why you need to first test your cohorts.”

COLLECT DATA FROM POTENTIAL CUSTOMERS

Customer surveys get a bad rap in the startup world. Many dismiss them when they don’t return accurate or sufficient results, but that’s often due to faulty survey design. “If surveys don't generate good data, it’s often due to user error. There’s a lot we want to know, but we make missteps in how we ask. We end up with 25-minute surveys with 45 different questions,” says Campbell. “Without thought to incentive or user experience, it’s no wonder we get back bad results and lose faith in surveys as a tool. But, if done correctly, they can be very powerful.”

Price Intelligently has sent upwards of 15 million surveys, and has studied what’s worked and not worked along the way. To start, Campbell recommends that you focus surveys to test two elements — features and price sensitivity — with a relative preference methodology. These should serve to test your hypothetical customer personas. The first survey helps rank your core features to determine relative preference by customer cohort, and the second focuses on overall price sensitivity — essentially a customer’s willingness to pay for the product.

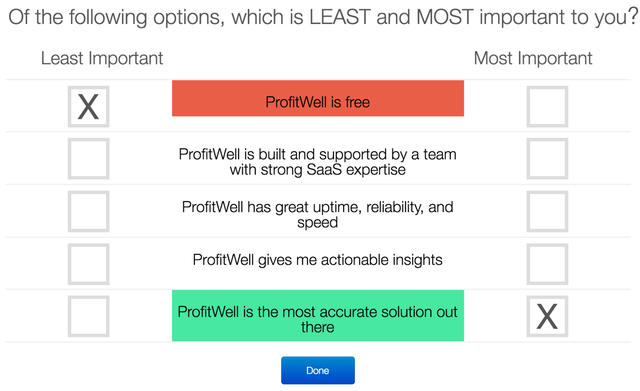

Feature preference surveys. It’s a challenge to extract people’s preferences in only a few questions. On one hand, you can ask a multi-step or multifaceted question, which are often time-intensive and burdensome for people to complete. On the other hand, you could opt for a more simple, lightweight question, which may not return the depth of response you seek. Ranking questions fall into the former category and multiple choice questions fit into the latter.

Instead, list a set of features to evaluate and hone in on the extremes. To test relative preference, ask two questions:

Out of these five features, which one is most important?

Out of these five features, which one is least important?

“In two quick questions, you get the pulse of what’s most and least critical relative to other features that may be on your list,” says Campbell. “Now you have a strong sense of not only what will attract and repel different personas, but the features for which they feel neutral. You’ve extracted significant context in a low-lift way for the target customer and extracted another data point for your development team. Now it knows which features your target groups don’t value or care enough about to influence different behavior or purchasing decisions.”

The other part of the equation is cadence. “You’ll get a richer, more current understanding of customer preferences over time than in one fell swoop. It’s the difference between a time-lapsed video and a handful of snapshots. It’s more dynamic,” says Campbell. “We’ve found it’s most effective to send surveys with 3-5 questions every three weeks, than a longer survey every quarter. Shorter surveys can generate responses at four times the rate — or greater — at that cadence.”

One last point about relative preference questions: it’s vital to ask what they most prefer, not what they most use. “Usage doesn't always correlate to value. Note the features that they don’t really value as well,” say Campbell. “Take accounting software. Invoicing is typically the highest used feature, but workflow and practice management are often much more highly valued, because that's the sticking point in their business. Just because a feature, like invoicing, is always present and used in a system doesn’t mean that it will be the differentiating feature.”

Price sensitivity surveys. When you put out your questionnaire to determine your pricing, there are two parts that are critical elements. The first is your value metric or how you charge (e.g. per user, per hundred visits, per thousand views) and the second is willingness to pay, which helps determine threshold pricing. Here’s how to ask for each:

For value metric surveys, use the relative preference methodology. “You probably have some instincts as to what your value metric could possibly be. If you're selling an analytics product, you could do per user, per visualization, per gig of data or per integration. Let's say you have those four options to test,” says Campbell. “ Set up a relative preference question with each listed as a choice. Send those to customers or prospects and ask, out of those four, where do you derive the most value from this product and where do you derive the least?”

Even before you do a deeper analysis by persona, you’ll start to get a sense of general preference about the entire sample. “Perhaps people don't really care about users, but they do really care about the number of integrations and most of all about the amount of data flowing through,” says Campbell. “Eventually, this helps you map out how you're actually going to charge. The implication for getting this right is if you get your value metric correct, your expansion revenue becomes less of an issue. All of a sudden your small, medium and your large customers naturally fit on a spectrum and you're basically getting them at different points of value along a demand curve. Without this, you’ll end up charging Disney the same price as you’d charge Price Intelligently, even though we act differently on our preferences.”

Another pitfall is blindly following traditional value metrics. “In B2B, there's this archaic belief that per user is the best value metric, because everyone sold licenses back in the day. Companies sold by the seat because they were physically given a disk or had to grant access or make a data transfer to each user,” says Campbell. “When SaaS emerged, most people naturally kept the per license or per seat model because that’s what was always done. But the challenge — and the opportunity — with SaaS is that you can be very flexible with how you’re charging."

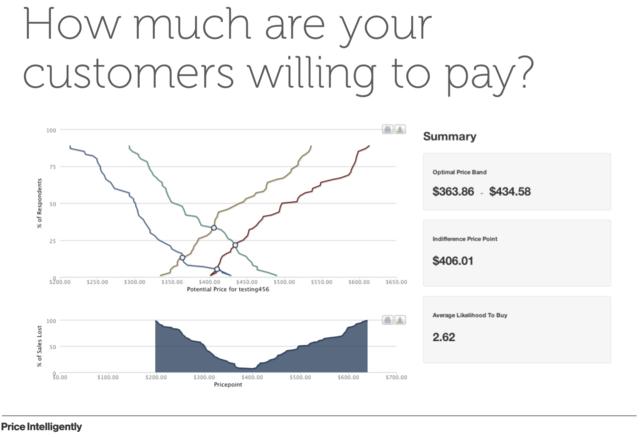

There are a lot of different ways to test willingness to pay, but Campbell has had the most success with a simple set of asks. “With these questions, you're not necessarily trying to get perfect price points. You're trying to figure out what the price elasticity looks like. You never want to ask someone point blank: how much should this computer cost?” says Campbell. “As I mentioned, our human brains just don't naturally understand the intrinsic value of an object. We know it’s worth across a spectrum. I know my computer’s more valuable than a pencil, so because of that psychological phenomenon, we should ask ranged questions.”

So, rather than ask how much a product is worth, ask these questions:

At what point is this way too expensive that you would never consider purchasing it?

At what point is this starting to get expensive, but you'd still consider purchasing it?

At what point is this a really good deal? (You'd buy it right away.)

At what point is this way too cheap that you'd question the quality of it?

“That last question is almost more important than all of the other questions because you’ll figure out your bottom limit,” says Campbell. “It’s critical not only because of pricing, but trust for your product. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve talked to a company and people just don't trust its product. It does plenty of cool things, but it’s five bucks a month. It just doesn't make sense to people. Now, those are good situations, because if you double the price, or increase it by a multiple, you'll see conversion go up — as people trust the product — and revenue rise.”

If you’re unsure of the stretch of your price elasticity, pick up the phone and call a few early or potential customers. “From those feelers or initial survey results, a ladder will start to form. You’ll see that a good deal for your product is $100 — which you could choose to optimize for adoption — and that you’re getting expensive at $200, which you could select to optimize for revenue. All of a sudden, you’re on the way to a deeper analysis, which will get more sophisticated when you get 50, 100, 200 responses to these four questions. But you’ll start seeing valuable, directional trends as responses trickle in.”

Two Approaches to Launch Surveys

If that seems like a lot of work to release these two surveys every three weeks, there are other ways to gather this information. “I know that running these logistics on a budget is challenging, so don’t be penny wise and pound foolish. Even if you’re starting out, and for $10,000 you can save 12 months of time, it should be a no brainer,” says Campbell. “I’ll admit that when Price Intelligently launched, we balked at that kind of tradeoff. Cash flow’s super important, but it ended up being more expensive not to get these data points on our customers. So don’t be afraid to spend a bit of time — or a bit of money — on these efforts.”

If the issue is getting large enough sample sizes for each of your customer personas, there are a couple of companies that can help. “Instantly, formerly uSamp, Fulcrum and a few other companies provide market panelists, so you can get responses from a soccer parent in Kansas or a Fortune 500 CIO. If you’ve got a consumer product, there’s no excuse for not doing this type of research,” says Campbell. “The audiences can be a bit more limited when you get into B2B enterprise software, as there’s not as many buyers, but you can still use these services.”

If this still feels like too much of an investment, just start small — but don’t expect a to get a full picture of your customers personas immediately. “That may mean one question per quarter, starting with what’s most preferred out of five features. Then the next quarter you do the four questions on pricing. Then the next you ask about the preferences for annual versus quarterly versus monthly billing,” says Campbell. “Like puzzle pieces, all of these will add up over time.”

What you want to avoid is the sudden realization that you need to be charging five times more than you are and the mess of messaging this reality to customers. So bite the bullet early and do a comprehensive study or start rolling out a small set of feature and pricing questions every three weeks early on, ideally right after you’re hitting around $85K MRR — what Campbell sees as a good mark for product/market fit and the time to really start scaling. “Either way, don’t make this more intimidating than it is. I pitched in to help my mother with a side project, a little quilting company. We’re from the Midwest where quilting is a big hobby,” says Campbell. “I did some of her market research. Granted I do this for a living, but it took six hours of my time, end-to-end. I spent $1100 with Ask Your Target Market and got 600 responses. I had 600 target customers respond to a 15-minute survey that was 15-20 questions long. In no time, I got more research than most enterprise software companies have on her customer than they do on their customer.”

APPLYING YOUR FINDINGS

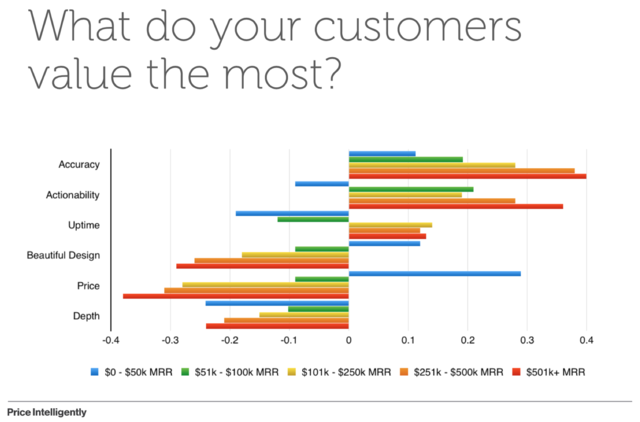

All the personas and surveys serve to fine-tune one key area: your pricing page. How you showcase and justify your pricing is the culmination of all these efforts and the lever for customer acquisition. But to get there, you need to first grasp the price elasticity of your offering.

Plot out Price Elasticity

After you’ve collected your survey results, use the data to determine your price elasticity of your offering by persona. “Price elasticity is a function of what your conversion is going to do relative to your price. In other words, it shows the demand for your offering changes as your price changes,” says Campbell. “Here’s a simple example. Say the Sunday edition of the Wall Street Journal or The New York Times is five bucks. Now you could do a good price elasticity study and find that if you increase the price to $10, you might lose 20% of your subscribers, but you’ll double your revenue. Then you have scenarios to compare to determine your price strategy.”

The reason why price elasticity is so critical for technology startups is because software doesn't have a finite cost, nor a finite physicality to it. “You can build unlimited software and sell unlimited licenses. But your addressable market isn't necessarily unlimited,” says Campbell. “So if you operate in a space that has a limited number of users, then you need to make sure that you either acquire most of them to boost revenue or get the highest price per customer for a portion of them.”

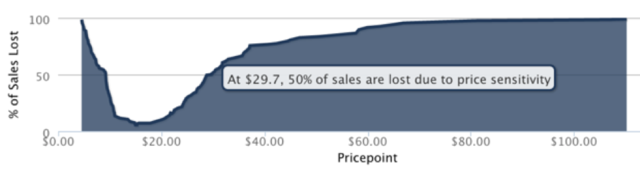

Startups can use the data captured by the same four willingness to pay questions to plot an elasticity curve. Once you make those calculations, here’s what it’ll look like:

Behold, The Pricing Page!

Once you’ve mapped your price elasticity curve, you can now refine each buyer persona by their feature preferences and willingness to pay. “Now you have an updated sense of the value for and motivation to buy for each group. You knew theoretically that everyone is at a different stage, but now you can track tipping points,” says Campbell. “For example, the very early-stage startup that wouldn’t pay $1,000 for a product that would solve a lot of headaches, may now, as a growth-stage company, see the value of that price for the time it’ll save. That's why you need to collect this type of data over time — to know when Mid-market Malik’s willingness to pay is actually five times that of Start-Up Susan, which may change your entire strategy.”

A key step to monetizing users starts with how you set up your pricing page. Here are a few of the more common traps to avoid from the beginning:

Death by check marks. “Pages with columns of check marks delineating each package is the first sign of a pricing page that’s likely built on little buyer research. They’re often designed and organized with the products in mind, not the people purchasing them,” says Campbell. “It’s not typically intuitive what the material difference is between the tiers, which is a big problem if you hope to have a touchless or semi-touchless sale.”

Mind your 9s and 5s. “There’s much misinformation on pricing out there. Common gimmicks dressed up as 'pricing hacks' include: End your prices in nines or fives. Or put the most expensive plan on the left instead of the right,” says Campbell. “Some of those techniques may make small differences, but are not substitutes for the basics and won’t generate more customers over the long run. Avoid micro-testing prices in lieu of more a wholistic process to build a pricing strategy.”

Use your customer personas as the foundation of your pricing packages. “Remember those initial hypotheses on buyer profiles that you refined with customer surveys? Use those to build your different columns,” says Campbell. “Your customer should be able to go to your pricing page and understand the difference between each of the plans in under 20 seconds. Enterprise Ernesto should be able to find the enterprise plan, and self-correct quickly if he’s looks at Startup Susan’s package.”

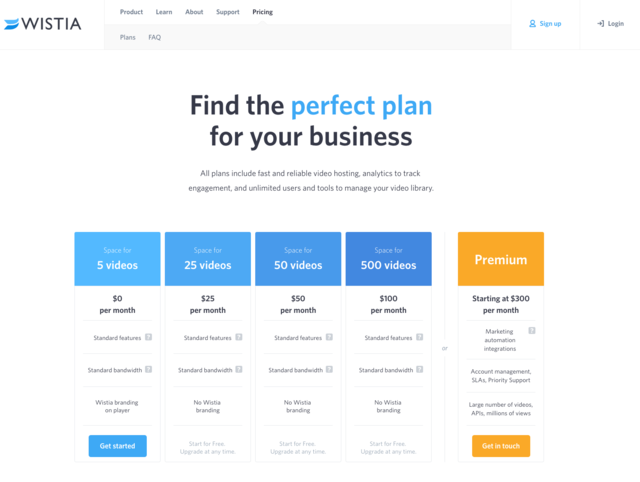

Here’s a good example from internet video hosting and analytics company Wistia:

A pricing page should be instructive and straightforward. “Wistia’s page is clear but not simple, and comprehensive but not crowded. It’s immediately apparent that its price is based on two axes: per video and per month,” says Campbell. “Extra information is listed in a FAQ that’s easy to locate in the menu bar or by hovering over one of the question mark boxes. It’s not only descriptive, but gives context. For instance, the pop-up box in the ‘Standard Bandwidth’ quadrant not only explains that ‘standard’ means 200GB of bandwidth, but that that allotment is sufficient for 93% of Wistia customers. The clean and compartmentalized pricing page shows that Wistia has done its customer research.”

When to Show or Change Your Pricing

Companies often ask Campbell if they should show their prices. “Early on, many startups don’t want to show prices — and that’s okay. Most don’t really know what they should charge, so they prefer to get intel by asking inbound customers some pricing questions,” says Campbell. “However, when you reach a point where you either want a touchless sale, then you need to show your pricing. If it’s not a clear number, such as in Wistia’s case, give a range. It doesn’t mean your pricing is negotiable — just that it varies depending on the customer. On the Price Intelligently pricing page, we give direction, not a figure. We’ll use a range, such as $20-30K, or a starting point, such as ‘packages begin at 45K.’ That allows people to self-filter and qualify themselves so no one’s time is wasted and opens a conversation to finalize the price.”

In terms of adjusting pricing, the rule of thumb is to refresh it every quarter or two. “A lot of people get nervous to change pricing because they don't want customers to perceive that they're paying more. The truth is that people understand that products cost money, but they need to get in a rhythm of how that changes as your product changes,” says Campbell.

As you improve your product and add features, show that those changes correspond with an increase in value and price. “First, your recurring feature preference and price sensitivity surveys should help verify and justify price raises, so you’re not operating in the dark. If pricing is adjusted on a regular basis, it trains your customers to understand that the value is going to be changing as the product is improving,” says Campbell. “The worst thing you can do is add so much value over the course of three to five years — even 12 months — and then all of a sudden want a big bump from your customers who have gotten used to paying a specific amount. That shock is what leads to pissed off customers and churn, not necessarily the higher prices.”

In reality, there's a lot of customers who are willing to pay more. “They just needed to be coaxed into it over time rather than one big bump. So what should you do? Every three to six months there should be changes, but you shouldn't be effectively raising the price every three to six months on someone,” says Campbell. “Don’t make people pay more for what they have, essentially lowering their value metric. Add in a feature to the enterprise tier and get people to upgrade. Or introduce a related plan with a slightly higher value metric and price. Those are ways that you can effectively make sure you're constantly evolving and optimizing your pricing.”

The one way to avoid any bad blood with your customers is to get pricing right as early as possible, so that you don't get into a situation where you’re raising prices and knocking on doors to get survival money. “You should be able to say to your customers, we’ve done X, Y and Z. This is the effective new rate for this price and it’s a long-year value metric because we had provided more value. Some will say okay right away, most will consider it, and some will ask you to answer a few questions,” says Campbell. “It’s not that you can’t come back from a long stretch without a habit of price increases, but it may be painful. Remember how Evernote was free for many years and then increased its pricing to $4 a month? Their churn on their free users probably took a big hit, but also there were people who were reliant on it and paid. Don’t wait as long as Evernote, and don’t make decisions based on your freeloaders, unless you have some way that you're going to monetize them eventually. Gradual price increases help gauge that.”

JUST GET STARTED

If readers take one note from Campbell, it’d be to get started now. Don’t wait for your product to be done to start sending out feature preference or price sensitivity surveys. After you release preferred features, don’t get intimidated by conversations with customers about price increases. Whether it’s early and just the founders or you have heads of product, sales and marketing, whiteboard your potential customers into personas. For each profile, assign your hypotheses of their preferred and least preferred features, as well as their willingness to pay. Then test your personas with relative preference surveys — whether that’s on your own and quarterly with a few questions or with the help of companies that can offer market panelists. Apply your findings to create intuitive pricing pages so clear that your customers can see themselves in them.

“The benefits of a well-researched, dynamic pricing page become apparent as customers find the right pricing packages for them and are open to price increases as new features bring increased value. However, clarity on pricing doesn’t just benefit Mid-market Malik or Startup Susan,” says Campbell. “It starts to unify the mindset and motivations of your team. If your surveys show that Enterprise Ernesto’s feature will increase his willingness to pay or LTV by 50%, there’s a clear, synchronized rallying cry for a specific feature. With a prioritized target, the team knows exactly what and why it’s about to build a feature. That’s an alignment that you can’t put a price on.”

Comments