A Founder's Guide to M&A

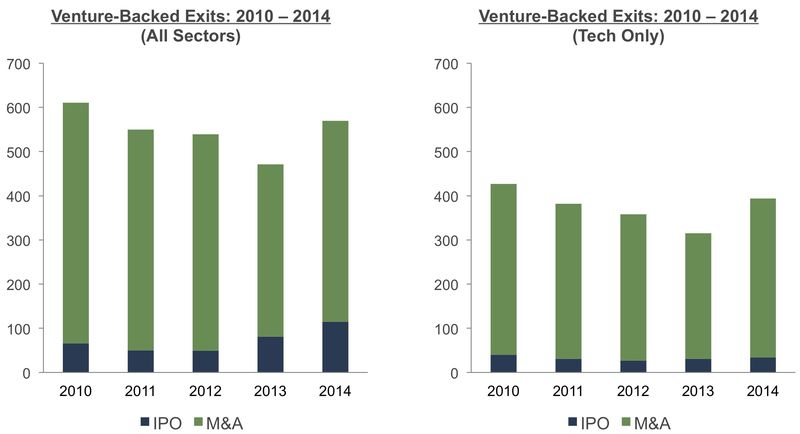

As a Founder of a venture backed company, eventually the question of whether and how to seek liquidity for your shareholders will come into question. This may come about because you are approached by a strategic acquirer or seek to go public. As shown in the chart below, given more than 90% of tech exits in the last 5 years are via an acquisition, the odds are by far in favor of M&A as the means of driving liquidity, although of course what the chart does not show is the thousands of companies that decided to keep building instead of selling in this period.

This data is consistent with our most recent experience at Flybridge: in 2014 we had six acquisitions and one IPO across our portfolio. So, if M&A is the most likely exit path for a venture backed company, what should Founders think about as they approach this process? Below I will explore questions such as 1) Should I sell my company?, 2) What is the best process to sell?, and 3) How do I achieve the best possible value for my business? This is a long post, so if you prefer the bullet points / presentation version, it is available here.

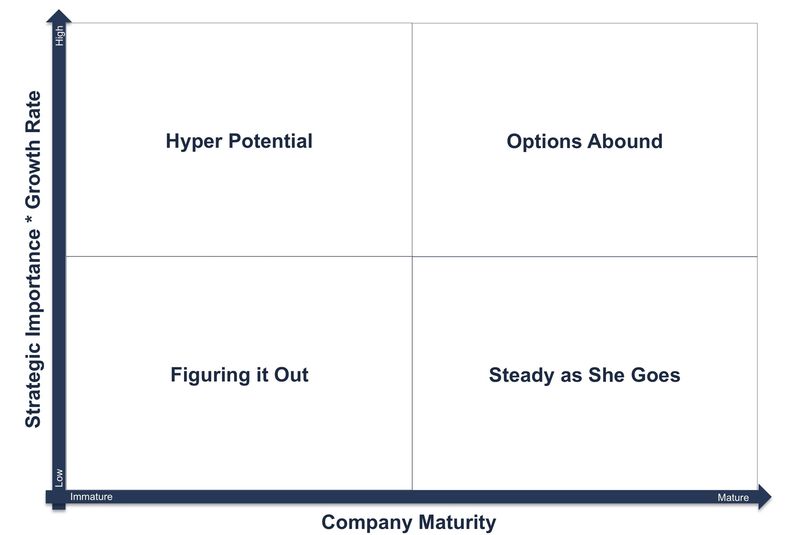

The first step is to take a step back and assess where you stand in the company building process. Is your company still relatively young and immature, but growing fast and strategically important to a number of acquirers (one of which may have approached you)? Or is your company mature, with a well understand and profitable operating model, but perhaps growing slowly and not terribly strategically important? Or, do you have the benefit of being strategically important, while growing fast, with a business model that is showing strong evidence of operating leverage and recurring revenue? Making a determination as to where you are along the axes of growth rate, strategic importance and company maturity will help inform your approach to M&A.

The intersection of these characteristics can be visualized on a 2x2 matrix as shown below. The Y-axis is a composite metric of both your company's growth rate and its strategic importance. Growth rate is pretty straight-forward and ranges from slow, less than 20% year over year growth, to hyper growth where the business is growing at more than 100% year over year. Strategic importance is harder to assess, but is a function of the market potential for your company, how the company fits with important high level industry trends, how threatening your success is to incumbent players in your industry, how easily your product or service can be sold through existing go-to-market channels for potential acquirers and whether your company will help drive revenues for an acquirer from other parts of their company, i.e. "drag-along" sales. The X-axis attempts to characterize where your company is in its development. These maturity characteristics include how well defined and understood the company's business model is, whether there is evidence of significant operating leverage where expenses are increasing at a far slower rate than revenues are growing, what characteristics the company has in terms of customer acquisition costs relative to the lifetime value of a customer, whether there are significant risks such as customer concentration or regulatory exposure, whether the business is profitable and cash flow positive and the strength and depth of the management team.

While the matrix simplifies a wide variety of different characteristics, it ends up creating four potential groups: companies that are still "Figuring it Out", companies that are showing "Hyper Potential", Companies that are "Steady as She Goes" and companies where "Options Abound". From an M&A perspective, each of these groups will lead to very different questions to ask on whether to sell, for how much and approaches and strategies to the M&A process itself.

Figuring it Out:

For companies in the Figuring it Out phase that are still early, not yet growing super fast, and are not strategically important, the critical questions to ask relative to M&A relate to how much runway you have and can more capital be raised (for example, if you have 6 months of runway and no clear path to raising more money, joining forces with another company via M&A starts to look like an important strategy). In addition, understanding why the company is not growing faster is an important question as it could be driven by a market that is slow to mature, which is harder to change, or internal execution issues, which are equally hard to change but at least within your control. A related question is whether, if you are successful in driving growth and can figure out how to get the resources to do so, is the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow still attractive, or have you lost faith. More broadly, this speaks to your team's motivations and desires. Is everyone still in the boat, or are you at risk of losing critical team members? Do you all want to stay together, but the collective risk tolerance is such that being part of a larger company would be better? Or does the idea of being part of a bigger company give everyone the shudders?

In the Figuring it Out stage, the answers to these questions will lead the the conclusion to keep pushing ahead or to look to be acquired. If the conclusion is to look to be acquired, the process in this stage is on one hand the easiest in that there is likely a broad universe of potential acquirers, but on the other hand the hardest as there may not be a compelling reason any one of them to need to own your company. This suggests that the process will be very customized, company led and relationship driven as you seek to demonstrate core value that you and your nascent product or service can bring to the table. As a result, there is not much of a role that an investment banker can play, although a third party consultant or adviser might be helpful with introductions or unique insights into companies you don't know well yourself. Likely valuations at this stage can range from modest acqui-hires to reasonably attractive outcomes if you are able to articulate a combined growth story that gets several acquirers excited such that you can get a little competitive bidding going in the process. Apart from a competitive process, other important valuation drivers will be the strength of your team, the willingness of critical members to stay with the acquirer and for how long, and whether you can identify ways your company will help create new revenue opportunities for the acquirer.

Hyper Potential:

Hyper Potential companies that are showing rapid growth in important market segments that are strategically important to potential acquirers are the companies that are most likely to see inbound acquisition interest, and whether to entertain these offers is often the hardest question for Founders and their Boards to consider. At the extreme, make the right decision and you look like SnapChat turning down a billion dollar plus offer only to be valued a year later at more than ten billion or, on the other hand, Groupon turning down a $6 billion offer and struggling to ever come close to that value even after significant further dilution. The critical question to ask at this stage is how realistic it is to move up the company maturity scale - in other words is there a case to be made for, or evidence of, a wildly attractive future business model. Related questions include how much capital and associated dilution will be required to pursue the opportunity and how this relates to the potential value of selling now. Further, some market segments that seem unlikely to support public companies go through a game of musical chairs whereby several companies could be competing for a limited number of acquisition chairs and thinking through do you want to be the first to sell or the last, can have huge bearing on valuation in both directions. Hyper Potential companies, by definition, have multiple alternatives, so the most important question is ultimately what motivates the team. My partner Jeff Bussgang previously wrote about this here, but the question comes down to the passion you have for the business, do you want to go out and change the world or is having a good win more important? Will the acquirer help you achieve that dream or screw it up and, conversely, if you stay independent can you and your team take the company forward for many years, and if you can't and lose control down the road, do you care?

If you are running a Hyper Potential company and you decide to sell, the process tends to be relatively fast and the buyer universe narrow. There are very few companies that can pay the super high-valuations (by any traditional valuation metrics) required to make it worth selling at this stage, so the likely buyers are the mega-cap public and private companies and it is more likely than not that the process actually started with an inbound approach by one of these companies. Moving forward with only one horse in the race generally does not make sense, so the jujitsu required is to quickly spin up some competing alternatives generally by leveraging the team's contacts and relationships. Given a quick relationship driven process, our experience has been that investment bankers are more likely to interfere in the sale of a Hyper Potential company than they are to add value. The key to driving a high valuation is, instead, making the case directly that you fill a CEO level priority for the acquirer, having multiple suitors where this is the case and being willing to walk away from the negotiating table, perhaps several times, if the offers are not at an acceptable level.

Steady as She Goes:

Mature companies that are growing steadily don't necessarily have to sell at any particular time as they are often profitable with solid business models. As a result, thinking about market timing is the most important consideration for these companies. If you are coming off a string of good quarters and the valuations for your comparable companies are increasing, it may suggest the time is right to look for an exit, while similar good performance in a tough market environment would suggest sitting tight. In other words, 2009 was a lousy time to sell if you did not need to, but 2014 was a pretty good time to look for an exit. Other considerations to think about in terms of when to sell a Steady as She Goes company are what risks there are to the downside - such as changing competitive environments, margin pressure, macro-economic risks specific to your business or regulatory changes that could be forthcoming - and what opportunities there may be to the upside that will bend the growth curve in a positive direction such as new product launches, new markets that are just being opened or potential opportunities to make acquisitions instead of being acquired. Important questions for the team to ask themselves is how motivated they are by the day to day running of the business and can they see continuing to do so for the next few years to come.

If the decision is made that the time is right to seek an exit for a Steady as She Goes company, the universe of potential acquirers tends to be the broadest of all the categories as the company could be a fit for small to large-cap public companies, larger private companies and private equity acquirers. As a result, the process tends to be more formal and involve broad outreach, an approach in which an investment banker can add significant value. Valuations for this type of company tend to follow more traditional metrics and models where the acquirers will be thinking about comparable companies and their own revenue or profitability multiples. The key to driving valuations higher will be a well orchestrated process, with multiple bidders, well articulated models of how the combined companies can generate significant synergies and a willingness to walk away and keep running the business if the options are not attractive.

Options Abound:

As the category name indicates, mature companies that are strategically important and growing fast, have numerous options. They can keep pushing forward as a private company, they can seek to go public or they can sell. This decision is ultimately a gut check on the business on all dimensions: does the market opportunity still appear to be unbounded, is there strong revenue visibility, does the business seem to be getting easier or harder as we scale, and do we have or can we readily build the right team? Further, it is gut check on whether the team is up for being a public company, and all that entails, and what risks could derail the business if it stays independent versus what opportunities are created by being public such as an easier ability to make acquisitions or the publicity and credibility that comes from being public. Having a clear point of view on the capital markers environment for your market segment and the relative values across the public markets, private markets and M&A markets as this will help you understand the financing tradeoffs. For example, in today's market you could argue that in certain segments the private markets are paying the highest values, followed by the public markets and then the M&A market, so this would argue that for a company with numerous alternatives, financing privately and building for an exit may be a better strategy than selling now, whereas a few years ago the M&A markets were paying the highest values.

If a company with multiple options does decide to put a toe into the waters of the M&A market, there is generally a mid-sized pool of potential acquirers from medium to large cap public companies to large PE firms. Given the considerations around the market environment and wanting to have an IPO as a credible option, having a strong investment banker to advise the company and potentially explore a dual-track IPO/M&A process is important. The key to driving a premium valuation will be all the process and synergy comments noted above for the the Steady as she Goes companies, but more important will be the credible threat of going public or raising a large private financing and being willing to drive the company forward independently for a number of years to come.

Across all the stages, the last and most important piece of advice is to keep building your business. An acquisition process can be wildly distracting, but even until the last minute there is a good chance everything can fall through, so figure out how to compartmentalize the efforts to make sure you don't sacrifice your company's potential along the way.

Hopefully this provides a useful framework for thinking through the issue of whether and when to sell your company and how to best approach the process and drive value once you do decide to sell. Once in the process, there are dozens of other considerations in terms of negotiations, structure and terms, but those can wait for another post!