Where Does VC Money Come From? (Flowchart)

This post was originally published on the personal blog of NextView founding partner Lee Hower. Lee’s posts also appear regularly on View From Seed. Subscribe here for more.

Most folks reading this will know that many startups were built in part with the help of venture capital. Most attention goes to tech companies ranging from Google to Genentech, but some non-tech companies like FedEx and Starbucks also raised VC early in their lives.

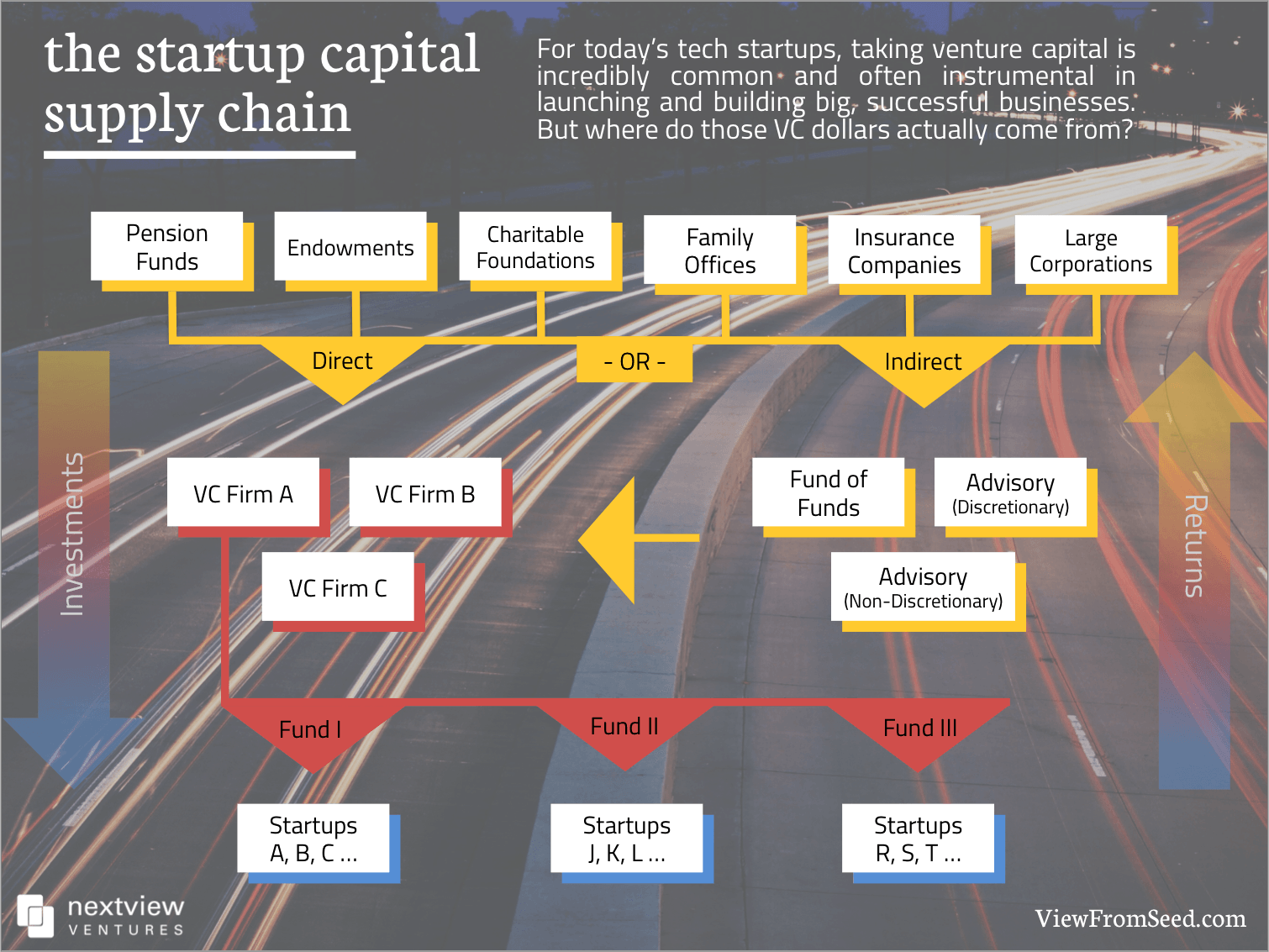

However, many folks probably don’t think about exactly where those VC dollars that help fund startups actually come from. So I wanted to dive a little deeper into what I call the startup capital supply chain. I’ve had a version of this post in my “drafts” folder for some time, but the confluence of three unconnected things (more on these later) prompted me to finally finish and publish it.

So where did that dollar that a given VC invested in a startup ultimately originate? Well it may be useful to illuminate this discussion with a chart.

(Click the image to view a larger version.)

Most of the dollars a VC firm invests come from outside limited partner investors (LPs). The actual partners of a VC firm (GPs) will typically invest a minimum of 1% of the total size of their fund,* though frequently this percentage is substantially higher (especially in many of the best funds).

The nature of LP investors can vary widely, but the bulk of the capital in the VC ecosystem comes from large institutions like pension funds, endowments of universities and hospitals, charitable foundations, insurance companies, very wealthy families (aka family offices), and corporations. A smaller portion of the total capital in the VC ecosystem comes from high net worth individuals. Very small funds may not have any large institutions as LP investors, just individuals, but even the largest and most established VC funds often have “sidecar” funds to enable a select group of individuals to invest in their funds (typically entrepreneurs the firm knows well).

To better understand VC capital, let’s look more closely at the various types of institutions (LPs) and their raison d’etre:

Pension Funds

Defined-benefit (DB) pension funds are the entities which pay a fixed pension amount to retired employees of a particular organization. There remain many corporate pension funds still investing in VC, though a lot of DB pension funds in the private sector are no longer enrolling new employees. Today most corporations have 401(k) style defined contribution programs where employees pay a fixed amount and the performance of their investments determine the amount they have upon retirement.

For public sector roles, such as government employees, teachers, and firefighters, DB pension funds are still the norm, and many public pension funds still invest in VC funds (though some of these are very large entities, making scale an issue, which I’ll discuss more below).

Some VC firms have eschewed taking direct investments from public pension funds, as state laws now sometimes require these pension funds to publicly disclose information about their investments that VCs consider sensitive, confidential info, like fund-level returns or individual companies in the portfolio.

Endowments

Endowments are the funds established by universities, hospitals, museums, and other non-profits to invest for the long term. The income these investments generate then help fund the operations of those organizations or capital investment (e.g. new buildings, etc).

University endowments are one of the main categories of LPs for VC funds, though there are also endowments for other kinds of organizations that are investing in venture.

Foundations

Large charitable foundations like the Ford Foundation, Carnegie Corporation, Kresge Foundation, and many others invest in VC. These foundations then support other non-profits with the investment returns they generate.

Family Offices

Wealthy families arguably created the VC industry both directly and indirectly. Some of the oldest VC firms were essentially the direct investment arms of wealthy families like Bessemer Ventures (originally an outgrowth of the Bessemer Trust established by the Phipps family) and Venrock (originally an outgrowth of the Rockefeller family), though at this point both firms now have outside LPs that constitute the majority of their capital. Greylock’s first fund was also raised from a small handful of wealthy families primarily in the Boston area. There are different flavors of family investment offices today, some are “single family” offices which invest on behalf of one uber wealthy family and their descendants whereas others are “multi-family” that might aggregate the wealth of a number of rather wealthy but not uber wealthy families.

Insurance Companies

By nature of their business, insurance companies end up with very large pools of assets that they can then invest and use to pay out claims over the long term. A number of life insurance companies and a small handful of P&C insurers are active LPs in VC, though in general the overwhelming bulk of insurance companies’ assets are held in liquid investments.

Corporations

A handful of large corporations actively invest in VC funds themselves. This typically has a dual purpose: generate a return on the company’s cash while also gaining insight into new startups and technologies that may be of strategic interest to the corporation.

As a result, most Fortune 500 companies aren’t investing in VC, typically only tech and healthcare ones, and some obviously have their own VC arms (e.g. Google, Intel Capital). So there are a handful of VC firms that get a large portion of their capital from corporations, but in general corporations are a small fraction of the overall capital in the VC asset class.

Many large institutions from the list above invest directly in VC funds, but others from the same categories will invest indirectly through a range of different intermediaries.

Typically, there are four basic reasons why an organization would invest indirectly.

The first is a staff constraint. Some institutional investors simply aren’t big enough to have in-house employees to vet and manage a portfolio of VC funds. The definition of “big enough” varies widely but, generally speaking, entities that manage less than $1 billion in assets will often go the indirect route.

Next is access – some institutions may have staff but lack the robust network of relationships with the best VC firms to get access to their funds. The best VC firms have a large surplus of LP demand relative to their fund size, so a good intermediary may enable an institution to invest in higher quality VC funds than they would otherwise be able to do directly.

The third reason is less in the hands of these institutional investors, and that’s governance. In some cases, the rules governing how an institution manages its capital may actually require the institution to seek an outside third party’s advice when making specialized investments in “alternative” asset classes like VC.

Lastly, there’s the issue of scale. LPs typically seek to invest in a portfolio of several VC funds, not just a single firm. If you’re a comparatively small investor, you might be better off putting $5-10 million into a pooled vehicle that’s invested in a number of VC funds rather than putting it all just in a single fund. Similarly, large institutions with tens or hundreds of billions in assets such as the largest public pension funds (e.g. CalPERS, CalSTRS) or sovereign wealth funds (e.g. Singapore’s GIC or Temasek) may find it advantageous to make a single $500 million investment in a pooled vehicle rather than try to find many good VC funds to invest comparatively small (for them) amounts in.

What Are These Intermediaries?

There’s a wide range of intermediaries for venture capital and private equity investment, each with its own structure and business model. The main ones include:

Fund of Funds (FoFs)

FoFs take capital from institutions, wealthy families, and others, and then invest it in a basket of underlying VC funds. FoFs are typically structured as limited partnerships similar to a VC fund itself, and they typically charge an annual management fee and carried interest on profits – again just like the underlying VC funds in which they invest. Because of that structure, an investor in FoFs will end up paying more in fees and carry than if they invested directly in VC funds, but the benefits of access, scale, and staff often outweigh the costs for some potential LPs.

FoFs are typically a “blind pool” in that the people running the FoF have full discretion over which underlying VC funds they invest in, and so the investors in FoFs don’t know up front exactly which funds this will be (though they can look back at the VCs a FoF has invested in previously as a guide).

Advisory Firms

Advisory can mean a great many things in the VC LP world — there are lots of flavors of “advisory” firms. In general however, they can all be categorized based on discretion and specialization.

Some advisory firms have discretion over the assets they manage, meaning if LP X gives Advisory Firm A money to invest, then Advisory Firm A gets to pick and choose their VC fund investments. Other advisory firms are “non-discretionary,” meaning they vet VC firms and/or make recommendations to an LP, but ultimately the LP decides whether or not to invest in a particular firm. In addition, some advisory firms are highly specialized and just manage assets to invest in VC funds, whereas others advise on a broad array of assets ranging from VC/private equity to hedge funds to public stocks/bonds and so on.

It was the confluence of three unconnected things. First I read Semil Shah’s post reflecting on a recent GP/LP summit he attended. I was at the same event and Semil’s thoughts on “A dollar travels far before it reaches a founder” were spot on, but I wanted to elaborate a little more. Secondly we had our annual meeting with our NextView LPs the other week so some of this stuff was top of mind for me. Lastly I saw this tweet from Sequoia the other week, which put a spotlight on some of their LPs and why Sequoia’s exceptional returns over the decades have helped enrich non-profit causes.

Does any of this matter to entrepreneurs seeking investment from VCs?

I originally wanted to write this post to shed a little more light on how the supply chain of VC/startup capital actually works. I thought it might be useful, particular to entrepreneurs who may know a good bit about the VC business but perhaps not to this level of detail about where the dollars actually come from and how they get there. But it also got me thinking about Sequoia’s great causes microsite there. Do entrepreneurs actually care where the VCs they seek investment from get their funding? Should they care?

Anecdotally, I don’t think most entrepreneurs really care about this, and personally I’m not sure they should. I believe great entrepreneurs do (and should) seek capital from VCs they think will be great long-term, value added investment partners. Whether that VCs success benefits this LP or that LP in the long run doesn’t really matter. I don’t believe that non-profit LPs (e.g. endowments, foundations) are morally superior to for-profit LPs (e.g. family offices or insurance companies or corporations). I don’t think one can even parse non-profit LPs… is it morally superior to build a new cafeteria for Harvard undergrads (by growing the Harvard endowment) or to ensure a secure retirement for public school teachers (by growing CalSTRS pension fund) or to construct a new exhibit at the Air & Space Museum (by growing the Smithsonian’s endowment)?

At the end of the day finding a great long-term investment partner is what it’s all about for entrepreneurs. The definition of “great VC” will be situation specific… it might mean a VC that has a specific stage/sector focus, it might mean a well-regarded firm brand, it might mean a specific GP who has highly relevant experience, etc. I applaud Sequoia’s transparency about their non-profit LPs, but many entrepreneurs will continue to choose Sequoia because it’s a great firm that has backed exceptional companies… not because of where their LP capital comes from.

* The 1% GP contribution is a statutory minimum for the legal & tax structure of most VC funds. Again a lot of funds have the GPs investing substantially more than 1% of the fund.